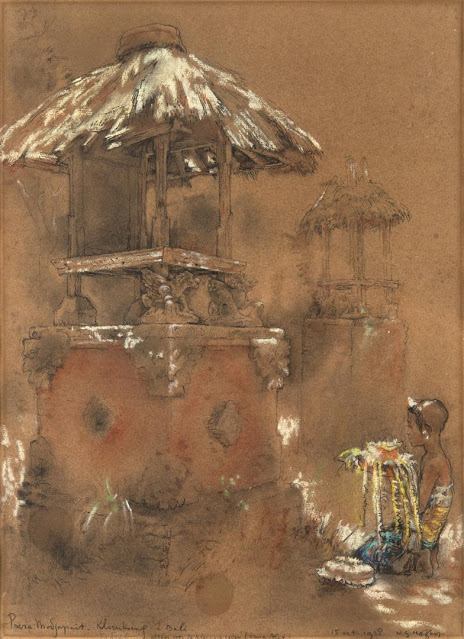

| Willem Gerard Hofker (1902-1981) ‘Poera Modjopait, Kloenkoeng Z-Bali’ |

Willem Gerard Hofker (1902-1981)

‘Poera Modjopait, Kloenkoeng Z-Bali’

conté crayon and gouache on coloured paper

41 x 30 cm

(15 October) 1938

signed and dated lower right

Note: there is a study of a girl on the verso, and a label on the backboard with a dedication to the previous owner

Provenance:

– property of the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (part of a commission from the KPM to the artist to make a series of drawings in the Dutch East Indies), Amsterdam/Batavia, 1938-1951

– acquired by Mr. J.L. Flanagan, United Kingdom, as a gift from the Board of Directors of the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij and the Koninklijke Java-China-Paketvaart Lijnen N.V., December 1951

– thence by descent to his grandson, United Kingdom

– private collection, United Kingdom

€ 10.000 – 12.500

“I heard today that I have been appointed “Tukang-gambar” (painter) for KPM in the East Indies for five months! Just like in thousand-and-one-nights! (including (…) fee and free travel!)”

(Willem Hofker, in a letter dated September 18, 1937)

In 1936, Willem Hofker was approached by J.H.A. Backer Esq., a high-ranked official at the Dutch shipping company KPM (Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij), to paint a portrait of the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina (1880-1962), and personally deliver it at the KPM headquarters in Batavia. Apart from that, Hofker was asked to travel through the Dutch East Indies, initially for only five months, to create ‘artist impressions’ of the colony. These drawings -they agreed on circa ten each month- were to be sent to Holland, enabling KPM to reproduce them in calendars, illustrated books and brochures. Hofker was aware that the shipping company had asked to draw and describe the culture, people and architecture of the Dutch East Indies in detail; consequently, Willem and his wife Maria prepared well for their journey in 1938, picking up some Malay words and sentences, and reading books by Karl With, Gregor Krause, and Miguel Covarrubias.

One may conclude that Backer personally lit the flame of Hofker’s inspiration to immortalise Bali.

Isaäc Herman Alexander ‘Eyk’ Backer, Esq. (1890-1964) was born into a noble Dutch family. He worked at the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij since 1914, and became acquainted with Willem and Maria Hofker in the 1930s. Being KPM’s general manager, Backer was promoted secretary to the Board of Directors early 1935. One month after his promotion, Hofker painted lovely miniature portraits of him and his wife Lilian. Subsequently, Backer invited Hofker to immortalise HM Queen Wilhelmina in 1936. Eventually, Eyk Backer was (co-)director of KPM in the Netherlands from 1945-1955. After World War II, he would continue to commission portraits by way of financial support for Hofker. Like Lorenzo de’ Medici was a mecenas for da Vinci and Botticelli, and like Mesdag for Mancini, Eyk Backer was a mecenas in a similar way for Willem Hofker.

And there was good reason for Backer to have developed this relationship. Born in The Hague in 1902, and trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam, Willem Gerard Hofker won second prize at the Prix de Rome in 1924, and became a renowned portraitist in the Netherlands during the 1930s. The 1936 KPM commission would prove to be a crucial turn in Hofker’s career.

Early 1938, after having delivered the Queen’s portrait at the KPM Batavia Headquarters, Willem and Maria Hofker spent four months travelling through Java, visiting Bogor, Bandung, and Garut. In June 1938, they decided to move on to Bali. Hofker was clearly inspired to draw and paint numerous Balinese temples and palaces. In October 1938, Hofker had already produced 85 drawings and 15 oils. Although he had a remarkable talent for portraiture, it was merely a way to earn a living. The models Hofker really loved were tireless and patient; Nature and Architecture. The current lot combines these beloved themes, and features a subtle portrait, on the lower right, at the same time.

‘I feel so at home here. It is strange that all these beautiful things are still made here every day. Sometimes one is reminded of the Italian Renaissance (…) or Roman reliefs of animals used as decorations in cathedrals, on capitols and in other places; this thousand-year-old culture has achieved the same high standard of visual imagery.’

(Willem Hofker, July 1, 1938, Denpasar)

The elementary shrine we see in the foreground, and repeated in the distance, indeed reminds of the way Renaissance architects like Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) coded the early Renaissance architecture; structural elements (the red bricks) differ in colour from the grey ornaments in the middle and corners. These grey, decoratively sculpted volcanic stone elements are specific motifs called Karang Curing (the upper part of a bird’s beak), and a rhombus shape in the middle which aesthetically complements the four triangular Karang Curingmotifs in each of the shrine’s sides.

The two singa, winged lions, looking at each other with one paw lifted, are typically used in Balinese architecture as pedestals (sendi) for pillars, thus symbolising support and stability.

The portrayed little shrines or pelinggih meru are in fact seats for gods or ancestors’ spirits, who will temporarily reside within them. The early morning backlit situation, suggested by Hofker with some touches of gouache, emphasizes this spiritual atmosphere. Its roof-like tiers (tumpeng) are always odd-numbered, going from one to eleven levels. As a symbol of the holy mountain (meru), the more levels of tiers the pelinggih meru, the holier the residing god or spirit. Both pelinggih meruinside the ‘Poera Modjopait’ are modest one-tier ‘shrines for smaller gods (Dewa Alit)’, according to Hofker’s annotation. We see a kneeling Balinese child honouring or paying tribute to these gods. Its bald head indicates a ceremony called ngutangin bok, during which a young child’s head is shaved to symbolise purity. The offering (canang sari) the child is holding is made of palm or coconut leaf, filled with various flowers and kepeng coins. Most elements of such an offering refer to the trimurti, the three major Hindu Gods Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma.

We seem to have come full circle. In 1936, Eyk Backer commissioned Hofker to make drawings of the Dutch East Indies. ‘Poera Modjopait’ was one of them, diligently sent by Hofker from Bali to Amsterdam. In December 1951, the same Eyk Bakker, together with drs. L. Speelman, director of the KJCPL shipping company, presented the current drawing to mr. J.L. Flanagan ‘as a token of their lasting friendly feelings’. It was their own canang sari; a Western way of paying tribute to a well-respected colleague, and to a well-respected ‘tukang-gambar’.

Literature references

– Hofker, S., Orsini, G., Willem Gerard Hofker [1902-1981], Waanders de Kunst, Zwolle, 2013, pp. 28/111.

– Covarrubias, M., Island of Bali, Cassell and Company Limited, London/Toronto/Melbourne/Sydney, 1937, pp. 129-130 / 183-185.

– Brinkgreve, F., W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp en zijn vorstelijke leeuwendoosje, in: Aziatische Kunst, 36, no. 3, September 2006, pp. 2-15.

Gianni Orsini MSc., October 2020

More information about our auctions of Indonesian paintings:

René de Visser

Zeeuws Veilinghuis – Zeeland Auctioneers

rene@zeeuwsveilinghuis.nl

www.zeeuwsveilinghuis.nl