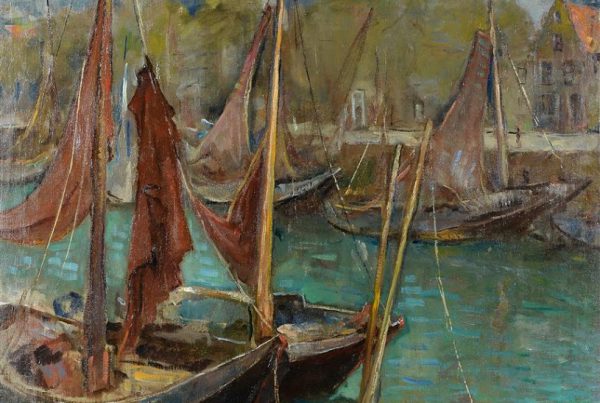

Exhibited: Hultbergs Konsthandel, Stockholm, Sweden, October 16-30, 1948,

No. 15, as ‘Helig Procession I, Bali’.

Provenance: Private collection, Sweden, Private collection, granddaughter of the artist, Switzerland.

“These works present a typically Oriental vision where shade and soft tonalities do not exist, where everything dances and whirls, where nature, people and objects are like motley spots of colour fading away into a blazing, all-absorbing light.” (De Gentenaar, 10 January 1950)

Ngaben is a unique and world-famous cremation ceremony that is only performed in this specific way by the Balinese people. Overall, the ceremony comprises three phases: the funeral (awaiting an auspicious day for the cremation), the cremation ceremony itself which takes place at the end of the procession that Adolfs depicted here, and the ‘purification of the soul’, where the ashes are dispersed in the sea or the river.

During the most visually impressive part, the carrying of the deceased in an exuberant procession like this, two major structures are built. The first is the bade (or wadah), a cremation tower which in the painting seems to consist of nine roofs, the number of roofs indicating the social status of the deceased. The second structure is a lembu, a giant bull which holds the coffin with the dead body in a sarcophagus. Both structures are made of paper, bamboo and light wood, so they can easily be incinerated shortly after. In the painting, the lembu is carried in a large cremation tower with an elegantly decorated roof, while the slender tall bade can be seen on the right, majestically rising above the crowds while carried on the shoulders by numerous Balinese men.

Executed in 1947-1948, ‘Helig Procession, Bali I’ is a late, but very typical representation of one of Adolfs’ best-kept secrets, his Luminist period (1940-1947). Although Adolfs was very productive in the war years, unfortunately most of the works from that period would subsequently be destroyed in bombing-raids. Few works from this stylistic period have gained any wide renown, probably for this reason.

The works from this period possessed a strong dynamic quality, a subtle spark of tropical light. They distinguished themselves by their exceptional wealth and intricacy of detail. Not only had Adolfs’s interest in the human face grown, with increasingly portrait-like renderings as a result, but all the major and minor foreground and background elements were being thoroughly observed and comprehensively (if impressionistically) captured. Quintessential in the overall effect was the brushwork: Adolfs used forceful, short, mostly rectangular strokes, each subtly different in shade from the next, making faces gain a deep glow, buildings a rich texture, and backgrounds a fervid flamboyance. Typically, the sky in Holy Procession, Bali is filled with a pattern of concentric brush strokes, guiding the eye toward the procession and the people swarming around it, and adding to the dynamic character of the painting at the same time. Undoubtedly, this style period produced a number of absolute highlights in Adolfs’s oeuvre, of which Holy Procession, Bali is a fine example. (ref. Borntraeger-Stoll/Orsini, 2008, p. 339-344)

“Adolfs has fathomed the soul of the Javanese and Balinese people. He has vitalised and intensified his figures with no loss of tranquility. Perhaps that is the most striking characteristic of these canvasses: this silent activity, of posture rather than of motion, and of concentrated observation on an event rather than active participation in it.”

(Hengeloosch Dagblad, 15 October 1949)

Ultimately, there is a beautiful paradox in the present painting. To most western people, a cremation ceremony is a sad event, with family and friends mourning over the loss of their loved one. However, for Adolfs who was born and raised in Semarang, and having lived in the Indies for over 40 years, it was common knowledge that Ngaben represents a celebration of a beautiful life, transcending to a next life. Especially this ‘holy procession’ symbolizes the moment the soul of deceased will be freed forever, or at least until the next incarnation. For this reason, Adolfs consciously used bright colours, forceful strokes, suggesting a cloud of sand and dust from the marching crowds, thus creating a festive dynamic that exudes the very sparkle of Life.

Gianni Orsini, November 2016